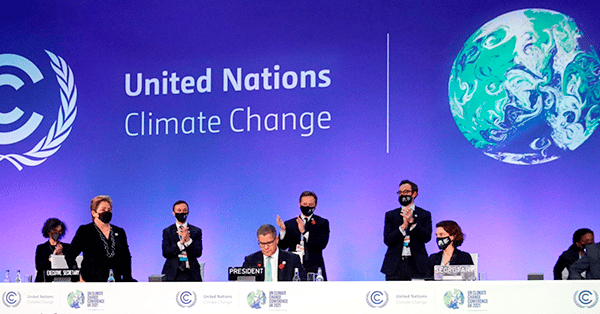

There were truly transcendental results in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, at COP 27, which ended a few days ago. Although there may be different assessments regarding their implications, to a large extent, the advances are linked to arrangements on the availability of financing for climate action in different areas.

Undoubtedly, from the immediate perspective of international climate regime building, the most notable decision was the creation of an international fund to address payments for so-called loss and damage, and to support victims of climate disasters, especially, but not only, in small island states.

This issue had been delayed for nearly thirty years in the negotiations of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, since the proposal by Vanuatu, a Small Island State, in 1991 for the creation of a United Nations fund to help deal with the consequences of sea level rise. This issue, which was a source of growing political controversy and which developing countries felt it was imperative to address, finally achieved a historic agreement.

Although it was considered essential by a majority of countries, it raised concerns in developed countries (including the United States and members of the European Union) and even in China about unlimited legal liabilities and claims for compensation for the occurrence of extreme weather events. The legal aspect was ably resolved in Article 8 of the Paris Agreement, which recognizes “the importance of avoiding, minimizing and addressing loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change”, while limiting the eventual contentious aspects in Decision 1/CP.21, associated to the Agreement itself, by which the Parties agree that “that Article 8 of the Agreement does not imply or give rise to any form of legal liability or compensation”.

The adoption of a fund to address payments for loss and damage was finally made possible, almost at the close of the COP, with a proposal that allowed access to the fund to all developing countries, with some independence of their level of vulnerability, leaving the door open to the contribution of other donors from a variety of sources, who are invited to contribute, including a variety of instruments and mechanisms for insurance, protection and taxation, as well as donations from developed countries. It remains to clarify and operationalize the processes of its financing in the next phase of the negotiation. Also what corresponds to the Santiago Network for technical support for the same purpose.

Traditional climate finance to reduce emissions and drive adaptation action has also been a very important issue at COP27. These negotiating efforts reflect the recognized need to scale up climate finance to developing countries from billions of dollars to trillions of dollars. The text of the coverage decision itself makes numerous references to the gaps between current flows and funding needs. The same estimate by the UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance estimates that those flows in 2019-20 only accounted for about one-third of all that is needed.

Multiple references to the finance issue during the negotiations range from calls for reform of the international financial systems to greater involvement of private finance to scale up low-carbon and/or zero-carbon investment.

Surely at the top of the concerns regarding funding needs is the pending $100 billion target that the wealthiest countries pledged almost a decade ago, which needs to be reformulated and would take place beyond 2025, while rebuilding confidence in the process.

Stay updated on the latest trends of Green Finance

Stay updated on the latest trends of Green Finance